Jeweler Jillian Sassone knows that every piece of jewelry comes with a story. Whether it be an heirloom, an inside joke, or a romantic gesture, the lore around its sentiment often outlives the physical piece itself. So what happens when that piece is lost, worn down, or broken beyond repair? That’s where Sassone comes in: her jewelry house, Marrow Fine, takes a story and gives it new life by reinventing its physical form. When our Chief Brand Officer Marc Duron had an heirloom piece to reimagine, he went straight to Sassone.

Grandma Olga is a “covered in diamonds, white-mink wearing, never seen in less than four inches, silk-and-gold-lamé beauty queen,” Marc Duron muses fondly. “Grandpa Ramón is stoic, and he just adores her. It’s something you can’t help but notice.” Duron’s maternal grandparents met in Arizona on the night of her quinceañera. It was a classic romance—a gentleman from the “other side of town” sees a blond, green-eyed beauty queen from across the room. Putting aside social conventions, he asked her to dance, “and, over sixty years later, they haven’t stopped dancing.” Duron’s wistful tone shifts as he adds, “Well, I guess until I saw him in the hospital.”

Since Duron was a child, he's been captivated by the particular boldness with which his grandfather moves through the world. As newlywed pioneers moving out west to set up a life in downtown LA in the 1950’s, his grandparents’ lives were filled with glittering theater marquees, trips to Vegas, and custom-made Yves Saint Laurent suits before they eventually settled in Arizona and set up a luxury home goods shop on Main Street in Douglas. One item that epitomized his grandfather’s personality: his wedding band. “It's a very old-school, 1950s Vegas, Rat-Pack ring with a giant two-carat diamond and a cool-etching pattern around the edges—which actually is much like him, and much like her,” Duron explains.

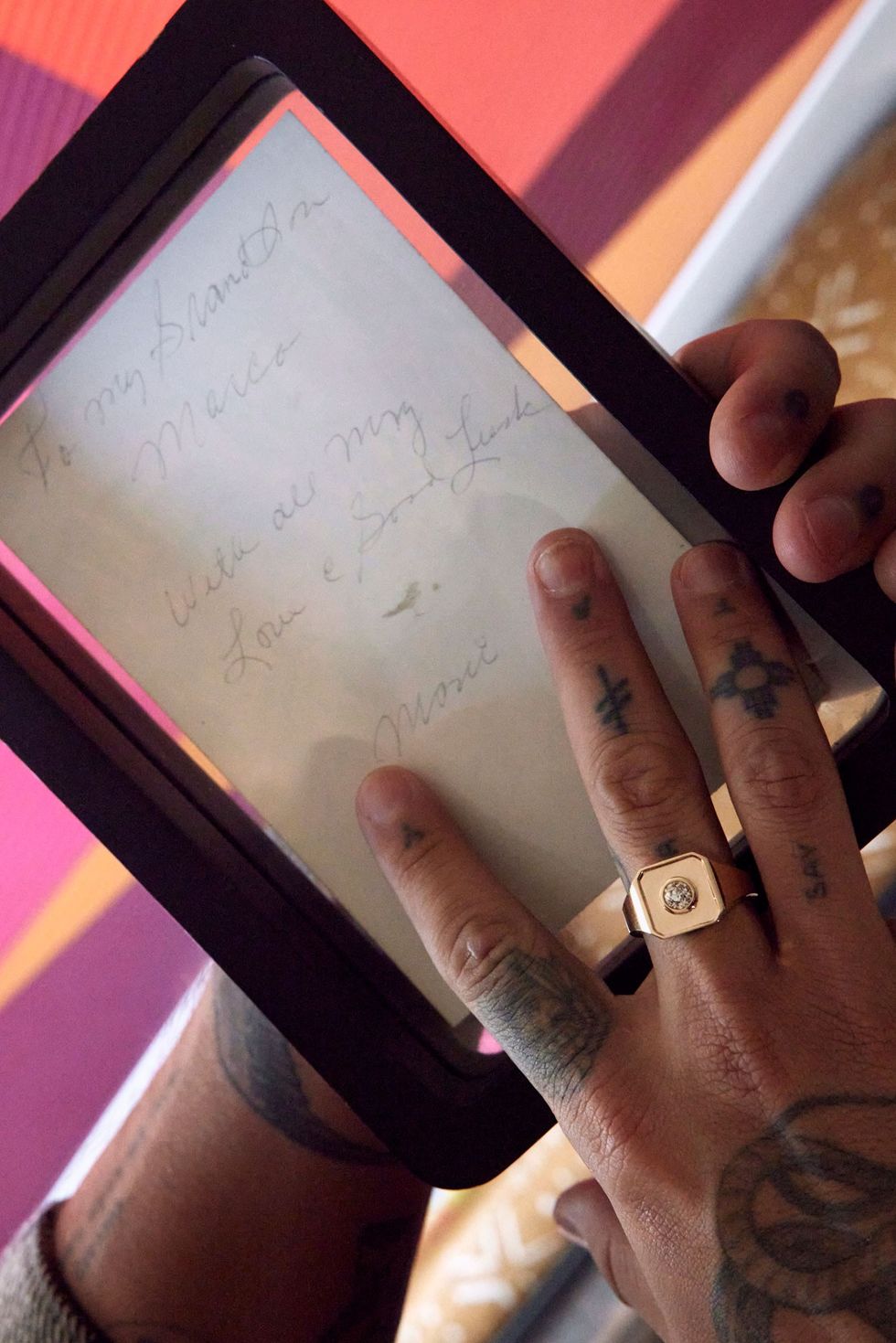

When his grandfather fell ill two years ago, the ring became a source of inspiration. “For me, the idea of the heirloom is something that you aspire to,” says Duron, “they don't just remind you of the person, but they remind you of the things that they have taught you. Whether [or not] they teach you overtly like my grandfather did about hard work, ethics, and morality, they also teach you things in life just by being themselves.” To Marc, his grandfather’s ring is an extension of his boldness and an emblem of the enduring love between true soulmates. With his grandfather still alive and wearing this ring, Marc wanted to create a companion piece while they still had time left together. Hearing about Duron’s profound attachment to his grandfather, a friend connected him with Jillian Sassone.

With some trepidation about trusting a stranger with such a loaded personal piece of jewelry, he was relieved to find that Sassone was “so beautifully, elegantly, quietly, compassionately, conversational” that he felt immediately comfortable sharing this story. When Sassone sent him the renderings of the design they created in homage to Ramón’s ring, he cried—“not just out of sadness but happiness as well. It was this duality of emotion.” Now that Duron has the finished ring, he hasn’t taken it off. “Every time I look at it, I remember great love, your soul being one half of a whole, and about hard work. Taking ownership of your mistakes. Loving fearlessly. These lessons from my grandfather inspire everything I do.”

To shed light on Sassone's unique service, we sat down to ask her about her very first project, the emotional highs and lows of grief work, and her collaborative process with Duron.

You came up with the concept for this service after you made a ring from your grandmother’s jewelry—can you tell me how this project came about?

Jillian Sassone: “I started about eight years ago when my grandmother, Mary, passed away. She was 90 and left me some of her jewelry. At that time, there weren't a lot of independent jewelry designers taking heirloom material. For a lot of jewelers at the time, if it wasn't up to a certain quality, they didn't want to touch it. This happened when I took my pieces to a few folks, and I was kind of deflated afterward. Then I knew what I wanted to do with it: I wanted to turn my grandmother’s earrings into a ring.

I created this ring using the opal from her earrings and some diamonds from a pair of earrings that belonged to my mom. To me, it wasn’t about how much the jewelry was worth—it was that I’d seen my grandmother wear it. It meant something to me and I think that resonated with folks. The first time I wore my ring, I went to get my nails done and told the manicurist about the process, and both gals on either side of me overheard the story. I left with both of them wanting to create rings with me. Within one day of having the ring, I already had two clients. It feels like this is the last gift from my grandmother. It was like her saying, ‘Let me give you this beautiful thing that you were meant to do.’”

How did the business grow from there?

JS: “Within a year, almost every night, I would have someone over after I put the kids down. After building up a client list, I took a leap of faith, quitting my day job as a medical device rep, cashing out a huge chunk of my 401(k), and then using half the money to build a little line. I used some of the money on a photoshoot and tapped some people with an Instagram following to help. That’s really how I built the business.”

How does the process work with your clients?

JS: “For whatever reason, I discovered I have a skill for looking at what people have brought me and envisioning what they could be. So if somebody dumps out the shoebox and there are 10 things before me, I’ll work with them to identify the best pieces, we talk about what they are drawn to the most and how those items play with each other in a piece.”

What has been one of the more challenging pieces a client has brought you over the years?

JS: “People come to me sometimes with their inside jokes—like something they want to engrave on a ring—and sometimes it’s things I would never repeat to anyone else, very intimate things. One couple had an inside joke that they would always say, “What’s up?” and the other would answer, “Chicken butt.” One day one of them said, “What’s up?” and the other said, “I love you,” for the first time. So they wanted to design an engagement ring that looked like a chicken. Thankfully, they were down for it to be an abstract concept, so I was able to make a cluster ring that, if you blurred your eyes, was vaguely in the shape of a chicken.”

What kind of emotional challenges have you run into?

JS: “I once had a pair of sisters whose parents were tragically killed in an automobile accident. They turned their mom and dad’s ashes into two diamonds and wanted to get matching rings. Whenever I get something like that, I can’t sleep for eight weeks until they have their stones back—even if I know they’re safe in the vault, I can’t sleep. I would say that was the hardest design I’ve ever done, just because you’re holding two people in your hands. While I was designing, I knew the parents loved country music, so I played it as I made the designs. Jewelry is already so sentimental and imbued with so much emotion, but what I wasn’t expecting when I got into this was how much grief work there would be.”

How do you navigate these intense emotional conversations?

JS: “I can hold space for it. It’s better than emotionally dumping on the hairdresser because we can channel that grief into the project. There are definitely times where folks come in, and they are still so much in that early stage of grief. In those moments, I hit the pause button and say, ‘You know what? Let’s not do anything yet because if I take this apart, I would hate for you to regret it.’”

What do you do if someone is bringing you an idea you think they will regret?

JS: “I’ll often give advice like, “Hey, I’d love to do this for you, but why don’t you come back in six months and just make sure it's what you really want since it’s so fresh and raw.” If you spent your whole life looking at your mom’s hand and seeing a ring a certain way, and it’s not the same anymore, there’s a possibility that you could regret it. There are other times when I see something so beautiful—like a handmade piece from the late 1800s—and I talk people out of doing projects because it’s so gorgeous.”

You don’t want to put carpet over the parquet floor.

JS: “Totally. And sometimes it’s different. Maybe if you went through a divorce, you look down at your ring, and you want it to have a new alchemy. Maybe a new metal so it’s a happy memory and not a sad one. Sometimes it helps to just add your own stylistic stamp on something like adding a stacking ring to an existing piece. Ultimately, I want the client to be happy, so I’m not going to take every project that comes my way, especially in cases where they might regret it.”

That must build a lot of trust between you and your clients, that you won’t take a project just for the sake of it.

JS: “I don’t want that on my conscience. When I meet someone, I hope that they’re going to be a client forever. You build that by treating them the exact same way you would want to be treated.”

Can you explain your collaborative process with Marc in recreating his grandfather’s ring?

JS: “I interviewed Marc to learn more about him and his style. He’s not necessarily a traditional jewelry guy, but he said, ‘In honor of my grandpa, who wears this big signet ring, I want to take a bold step. I want to wear something that honors him that is a bold statement piece.” His grandfather’s ring has some etching and flourish details, and I knew he didn’t really want all that—he wanted a big signet without the additional flourishes and something that would suit his lifestyle as an everyday ring.

“The stone that I selected for him is a really old diamond, probably cut in the late 1800s. It’s a European-cut diamond, about a half carat, with a gorgeous faceting pattern. He was really drawn to a clean look, so we designed a clean bezel with clean lines. It’s similar to his grandfather’s ring but also takes into account their unique personal styles.”

Why is jewelry so uniquely sentimental compared to other inherited items like tchotchkes, home goods, or clothing?

JS: “If you think about these things that we adorn ourselves with–they’ve been in the dirt for millions and millions of years. There is an energy to them, and there’s something special about them that draws you in. There’s something so personal about it being on you all the time. You wear it through hard times, fun times, and all your milestone moments. They are naturally imbued with such a sentimental nature.”

Are there ever pieces with bad energy?

JS: “Like bad juju? I know Emily Ratajkowski started this conversation about divorce rings, but they’ve been around for quite a long time. There are times when people have bad memories or feelings associated with a piece of jewelry, and it’s really therapeutic to take it back by standing in your power and saying, ‘I’m going to make this for me.’ You are able to reclaim the narrative. There is an alchemy to that and I’ve had a lot of clients that find it healing.”

You’ve never encountered an amulet with a terrible curse on it?

JS: “I have not so far. Thank god.”

As a kid, I read a lot of books and really thought amulets would be a bigger part of adulthood, but so far, I’ve never encountered one. Kind of a disappointment.

JS: “It really is. Don’t give up.”

Want more stories like this?

The Mother-Daughter Duo Behind Bernadette Talk Belgian Antique Markets, Printmaking, and Prada

I’ve Never Gotten Rid of A Piece of Dries Van Noten

Carine Roitfeld Values What’s on the Inside—That’s Why She Wears Really Nice Underwear

from Coveteur: Inside Closets, Fashion, Beauty, Health, and Travel https://ift.tt/d4nisXE

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment